Mindful U Podcast Episode 106. Bill Porter: Translating Poetry: Finding the Heart

The latest episode of our podcast with Bill Porter is available at Mindful U, Apple, Spotify, and Fireside now!

Did you know that translating poetry from one language to another is an art unto itself?

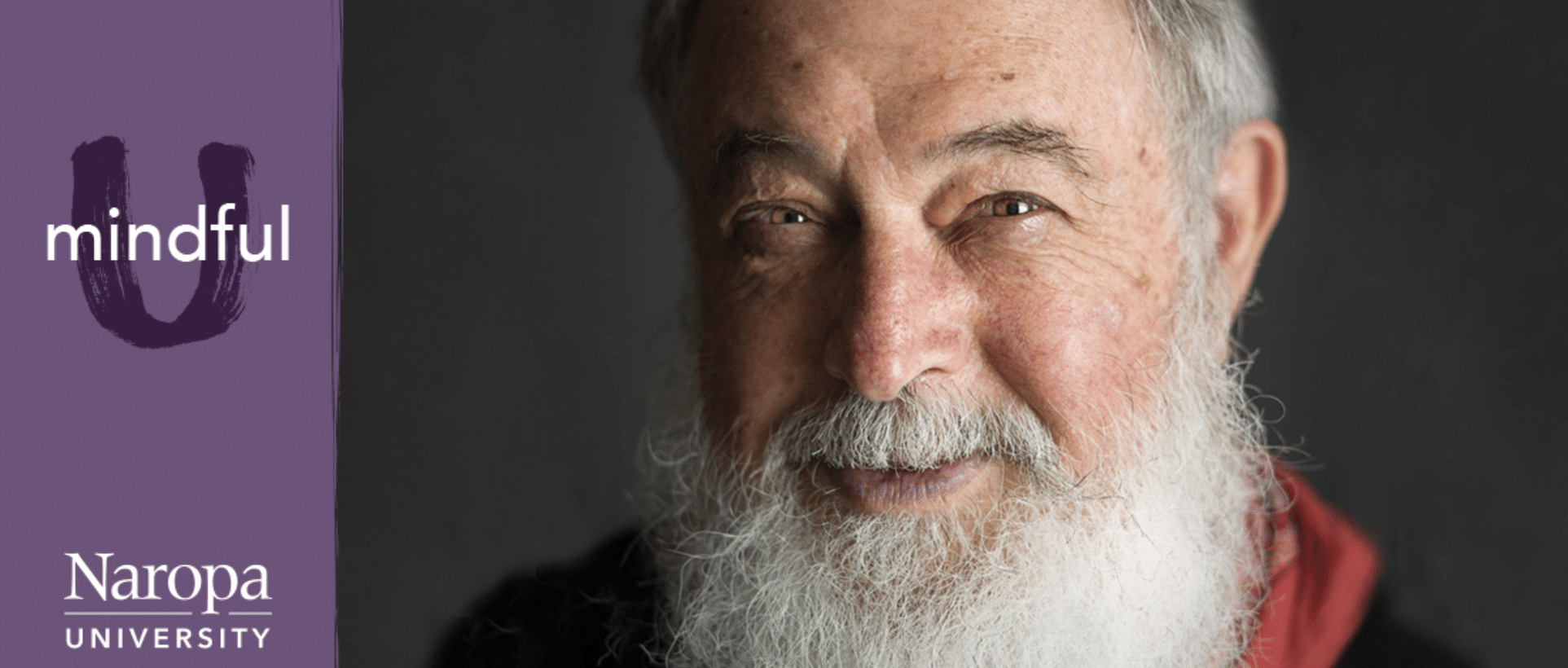

In our latest episode of Mindful U podcast author, translator, and veteran, Bill Porter, who goes by the pen name Red Pine, takes us through the process of finding the true heart of poem that’s hidden beneath words. Bill Porter was the 2024 Lenz Foundation Distinguished Lecturer. Special thanks to the Lenz Foundation!

Hear his journey of how he began translating thousand-year old Chinese poetry and Buddhist and Taoist texts, and how that has shone a light on the nature of language itself. As a translator, he sees language as an experience that cannot be replicated and perfectly transformed from one into another, but when we dance with the rhythm that’s behind words themselves, and immerse ourselves in the world view of another we can find the true heart and meaning of an author.

Find the title works of Red Pine below:

P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses

A Day in the Life: The Empty Bowl & Diamond Sutras

Trusting the Mind: Zen Epigrams by Seng Ts’an

Cathay Revisited & Dancing with the Dead

Stonehouse’s Poems for Zen Monks

Why Not Paradise

Full Transcript Below:

Full Transcript Bill Porter TRT 52:43 [MUSIC] Hello, and welcome to Mindful U at Naropa. A podcast presented by Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. I’m your host, David Devine. And it’s a pleasure to welcome you. Joining the best of Eastern and Western educational traditions — Naropa is the birthplace of the modern mindfulness movement. [MUSIC] David Devine: Hello everyone, and welcome to another episode of the Mindful U podcast. Today, we have a special guest speaking with us virtually today, and that’s Bill Porter. Bill publishes books dealing with Chinese culture and translation, which he does under the name Red Pine. In his early years, he served a tour of duty in the US Army from 1964 to ’67. After that, attended college at UC Santa Barbara and majored in anthropology. In 1970 he entered graduate school at Columbia University, while in New York, he became interested in Buddhism, and in ’72 he left America for a Buddhist monastery in Taiwan. In 1993 he returned to America, where he worked as an independent scholar, writing about Chinese culture and translating Buddhist texts and Chinese poetry. So welcome to the podcast. How are you doing today? Bill Porter: I’m great, David, thanks for inviting me. David Devine: Awesome. And you were telling me it’s a sunny day and you just can’t wait to get outside and do some gardening? Bill Porter: I can’t wait. I can’t wait because when things start to grow, you gotta act fast sometimes. David Devine: I know, right? I’ve actually realized that with my garden. What do you like to plant? What do you like to put in the garden? Bill Porter: Well, I’ve already planted snap peas about a month ago, and a bunch of spinach and different kinds of greens, lettuces and so forth. I’m now beginning the tomatoes — the tomato plants and planting some zucchinis. But anyway, there’s lots of work to do. Once you plant things in the ground, you don’t just plant them. You have to do other things to make sure that they’re okay. David Devine: Very true. Very true. All right, so to get started, when I was reading and researching you, I noticed you have, like, a very unique journey of your educational path, of your interests, and you know, just kind of like how you move. You started — you started with the army. You went to college, you got an anthropology degree. You fell in love with Buddhism and like spiritual content. And then, like, Chinese culture, you went to Taiwan and became a monk. And what I’m wondering is, if you can let our listeners know, what was that journey like for you? Like, where did the inspiration come? When were you triggered to, like, study anthropology, then you went, like, to Buddhism, then you, like, left the country. How did that all unfold for you? Bill Porter: Well, when I got out of the army, that was in ’64, I had flunked out of Santa Barbara in 1961, three years earlier, as an art — as an art student. David Devine: Oh no. Bill Porter: And then the next year, I went to Palomar College near San Diego, enrolled as a psych student, I flunked out. And the third, third year, I went to Pasadena City College as an English Lit student and flunked out and was drafted into the army. That was ’64 — March of ’64 and they were just beginning to send people to Vietnam, but they had a special program that I heard about. Normally, you get drafted for two years, but if you’re willing to add an extra year to your time of duty, you could get any training that you wanted, that they had available, or any duty assignment. So I added an extra year for Europe, and by gum, they sent me — sent me to Europe. So I — I went, spent three years there, but I wanted to go back and study again. I just wasn’t ready for college, when I started going to these universities and flunking out every year, I, just something was wrong. It wasn’t — it wasn’t — my head was in other — other realms. Anyway, in the army, I came to the conclusion that this life is — is precious, and I really didn’t know how I wanted to live it. And so I thought, well, if I study anthropology, I’ll get to study how many different kinds of people in the world live their lives. And I could choose one, or I could, you know, take a little bit from this one and a little bit from that tribe or whatever, and decide how I wanted to live this life. So anthropology was what I signed up for, and I got, you know, of course, interested in it and good at it, but I wanted to — after three years, I finally graduated and wanted to go study — I didn’t want to go get a job. I didn’t know what to do with a degree in anthropology. So I applied to Columbia University because they had the best graduate program in anthropology. You know, Margaret Mead was there, Ruth Benedict, a whole bunch of really great professors. So I applied to Columbia to study anthropology. I was only giving them, I think it was $175 a month from the GI Bill, and I needed more money, so I — I checked all the boxes for financial aid, and there was this one fellowship for an American citizen who studies a rare language. And I just read a book by Ellen Watts called, The Way of Zen. And it made wonderful sense. But that’s not the reason I thought to work in this fellowship is because that book had all these Chinese characters in it. I — the first time I’d ever seen Chinese characters, and they were crazy. I didn’t understand — I didn’t see how anybody could look at that graphic design and see something, book, you know, a tree or whatever. And so just on a whim, I wrote in the word Chinese. They gave me a four year fellowship to Columbia. It was a huge embarrassment, because I was such a fraud. I had no interest in China or Chinese or anything. But that was the fellowship they gave me, and it was — so it was the — my whole life was determined by a whim or — or an accident, karma, you could say. When I got to Columbia, I had to study Chinese as well as anthropology, and it was very painful. I was not that good at it, but I persevered. And yeah, as you said, when I was in New York, in Chinatown, I met a monk, and I started spending weekends with him, meditating, and so I really was impressed with what he had done with his life, and sort of the path he walked. And I decided that that’s the path I want to walk. I wanted necessarily to be like him, but living your life with the Dharma every day, that sounded like the way to go. Until I realized that continuing working on a PhD was — was ludicrous. And so after two years, I gave them back the fellowship, because it still had two years to run, and they could give the money to somebody else. And I went to Taiwan because I’d been studying Chinese. So going to Japan to study Buddhism didn’t make sense, or Southeast Asia Thailand. So in China, the Cultural Revolution was going on, so going to China, but Taiwan was — was perfect. And I, one of my fellow graduate students at Columbia, had been in Taiwan, gave me the name of somebody, and I went there. And I was never a monk, but I just lived in monasteries, and they just took wonderful care of me. They’d never seen a Westerner before, not like in Japan, where they have a system already set up, they can just plug you into it. So they let me pretty much do what I wanted to do. I’d take part in, you know, the ceremonies and so forth and — but I had a lot of time on my hands, and I started reading texts and finding a Chinese text in English translations. And I would see how the translator, you know, and how the Chinese were — text itself worked. Also, I got these bilingual texts of the — of the kind of Confucian classics, like the four books of Confucianism, and these histories of early — the early period of China, the Han Dynasty and the Tang Dynasty. Before I even really learned to speak very well, I got familiar with the classical textual language. And I was in the two different monasteries for about three and a half years, and never was so well taken care of, I always felt a little embarrassed about it, because they wouldn’t take any money. They just took great care of me. At a certain point, I decided it was time to go out on my own, and so that’s what I did. But before I did, the abbot of this last monastery had helped finance an edition of the poetry of Cold Mountain, Hanshan, and he gave me a copy before I left. And said, here you may look at these poems, you might like to translate some of them, and that’s what I started to do. So I got into translation and started translating the poem to Cold Mountain. I had no idea how you go about translating, but — and I — and I don’t write poetry, so I didn’t have any poetic skills. So it was — it was not the easiest road. And I can honestly say my — the first time I ended up publishing my translations, they were — they weren’t that good. When you translate, you go down a lot of dead ends, because there’s nobody that teaches you how to translate. Especially, how do you translate a poem, especially if — if you don’t have a poetic skills. But I was so impressed with the Chinese and with the Dharma in Cold Mountain’s poems, I really wanted to translate them. David Devine: Hmm, that’s interesting to think about, too. So it seems as though you had a wanting to learn Chinese, like read it, and then you got interested in the spiritual aspect of Buddhism, and then you went to China. And then, you know, you found a monastery, and they’re taking care of you, but then you’re learning how to translate it. So translating wasn’t a thing that you started with, it was more or less learning to read it? Bill Porter: That’s exactly it. I thought, by — by trying to translate, you learn better, than if you just read a text, you just, you know, you skim it over, skim through it, but if you’re trying to translate a text, you really go deeply into it. And especially because these, this was poetry. It was short. Poems were short, and only a few characters, so you just spent a lot of time with them. If you think — you could translate a poem in a day, but sometimes it would take a week because of what — what you would find there, and then how you try to render it. Anyway, it was — it was an experience that I became addicted to, the experience of translation, especially the translation of poetry or Buddhist texts. David Devine: When it comes to translating a poem, especially in a different language, like Chinese, because there’s like 200 characters in their language, and you’re talking about the abstractness of a poem? You know like you’re saying it takes a day to translate a poem. What is that like translating something that is abstract? Bill Porter: Well, when you translate poetry, you begin to realize the mercurial nature of language itself, especially poetic language. The language we use in prose is structural. It’s a noun, verb, object, and you know, it’s easy to see logical sense in a — in a line of prose or a paragraph of prose, but in a poem, lines are pretty open ended, and especially Chinese characters, because they don’t — very few Chinese characters, by nature, have a — are a part of speech. There are very few characters that are always — have to be a noun, or definitely a verb. Most Chinese characters are a little bit ambiguous. So there’s a lot of ways that you can, when you see all a string of five characters or seven characters, because most poems that Cold Mountain wrote were either five characters to a line or seven. So you see only five or seven syllables. As soon as you put one — one character next to another, you amplify the meaning of that first character and the second, because they all have different meanings. And how are you going to put them together? What’s the link here? And then you got suddenly five or seven together, and then you — you have to come up with a — with a way of trying to put yourself on the same page as the person who wrote that — that line. And so it’s a process of trying to match the rhythms that are going on behind the word, because people don’t necessarily write the poem is they — they feel it first. They’re inspired by something, by a scene that they’ve saw — they’ve seen, or an experience they’ve had with another person, or an insight into life itself or the world in which they live. So there’s something always going on behind the words. And so if you’re going to translate a poem, you’ve got to become more open to spending time trying to find this — this realm behind the words. So, I tell people, it’s like dancing with somebody. You don’t become the person you’re dancing with. You don’t — English never becomes Chinese, and Chinese doesn’t become English. A lot of people think that’s what translation is. You have to replicate the language somehow. Of course, that’s absurd, because languages are all different. They’re different ways of viewing the world and also different ways of expressing it, linguistically or grammatically. So it’s a process of trying to dance that dance that you find behind them, behind the words, where you accompany, use your — your skills in the English language to match that — that Chinese line. And of course, it’s not just one line, because when once you translate a poem, it’s a whole series of lines. There’s a voice. Every poem has a voice that runs throughout the whole poem. It’s a performance. And so as a translator, you have to perform the poem. But this is something that’s taken me years to develop, this ability, and every time I — every day I translate a poem, I have to redo it — I have to do it again from scratch. Just because I’ve translated a couple thousand poems and published them, doesn’t mean I’m going to be able to do a good job on the next one I run into, because it’s — they’re all just discoveries, and sometimes — sometimes you get it, and sometimes you don’t. David Devine: It’s interesting to think about that, how you can show up to a form of characters in a poem, and you — you translate it, and then you know, you go, take a break and drink some tea, go in the garden, check on your peas, and then you come back and you’re like, hmm, maybe this changed a little, maybe this changed a little. It’s like your collaboration gets deeper and deeper the more you sit with the poem, it seems like. And has that happened to you, where you’ve, like, translated a poem, and you come back to it and you’re like, whoa, I was way off. And then you translate it again, and you just — you just kind of deduce it down to, like, its characteristical states. Bill Porter: Absolutely, it’s like, for example, I don’t usually like to read the books I publish, for that reason. David Devine: I mean, you kind of did it, right, you read it in your mind. Bill Porter: Well, yeah, but I — if it’s — if it’s a translation of poetry, and I’ve done it the book came out a year ago or two years ago or whatever, I’m always going to open it to a page, I’m going to say, oh no. David Devine: You’re just going to critique yourself and be like, uh oh, I changed that word. Bill Porter: Well, yeah, I could have danced that better. It’s the idea that I could have done a better job. And that’s what it’s like being a translation of either spiritual texts or poetry that are profound. There’s a lot going on under the word spiritual texts and poetry. It’s not regular language. So you can’t — you can’t translate it, it’s all you look at is the — are the — is the surface — surface part of the word. David Devine: Yeah, interesting. It’s more metaphysical. It’s more spiritual. It’s — it’s not so like wood or it’s not like a material, you know, it’s not very factual stuff. It’s very in the mind, kind of floaty feeling based, psychological. Bill Porter: And also, these words that were put on page were put on page a year, a thousand years ago, maybe two thousand. And the way we speak is very different, and so, but you have no choice but to speak to your fellow — the people of your culture, people that you’re — you have this — you call language, and you’ve developed it ever since you were born, with your parents and your classmates and the media, all the influences on your own way to speak. So it’s — it’s going to be different from two thousand years ago in terms of how a line is put together, but there’s something behind the line that is the key, and so you don’t have to have the same order of words or concepts. There’s the heart to align, and, of course, a heart to a poem, and you that’s what you have to go after and try to dig out so that that you find something in the poem that you can dance with. David Devine: Interesting. You’re making me think about translating other languages that have poetry and sutras and spiritual texts in such a different way now. I like the idea of the dance, the collaboration, and it’s almost like you have to understand the writer and who they are, where they were, and what error they were writing in, to conceptualize the translating that you’re gonna go with. Bill Porter: Yeah, I’ve never translated anybody without going to the places where they lived in China. I visited the places where they live. I visited their home, the place where they lived, and also their graves and the mountains they — they wrote about, the rivers to get a sense — and also because if you go to a place in China where somebody lived a thousand years ago, there are going to be some people in that town who devoted their lives to that writer, that poet, and those people never get their stuff published. If you don’t go to that town, you’re never going to get this information that these local people all knew. They knew this — this guy, and they knew his poems, and they knew when he said this word or this phrase in that poem, he was referring to something that somebody just reading the poet — poetry itself would never get. And that’s why it’s really important translating somebody, especially in China, you really got to go to the places where these poems were written. See for yourself and meet with local scholars, local people who don’t necessarily get their works published. But do you know limited editions in the town. David Devine: Doing the good work, I see? So another question I had for you was, I notice when you translate Chinese texts and literature, you do it under the alias of Red Pine. And I’m curious if you can explain the idea of having an alias. And also, what does Red Pine mean to you? What, like why did you come up with that alias to write under? *Bill Porter: Well, when I went to Taiwan in the first place, I stopped using my name publicly, because the Chinese person wants to say Bill Porter, just like when foreigners come to America, they become John and Mary, or whatever. My Buddhist name, when I took the refuge in the Dharma in New York City, the monk there gave me a Buddhist name. Called it — it was victorious cloud in English, (Buddhist word for victorious cloud). So I was (Buddhist word for victorious cloud). And so in the monastery in Taiwan, also I was (Buddhist word for victorious cloud). And so when I left the monastery, I realized I needed a new name, a new Chinese name, because the (Buddhist word for victorious cloud) is a, you know, it’s a spiritual name. I need a name for the regular world, the working day world. And so I was in the market. And so I was in a bus one day, and it stopped right next to this billboard advertising Black Pine cola. And I said, that’s the name, but the colors wrong. That’s a Japanese color, black, red is the Chinese color. It turns out Black Pine cola was a — was a Japanese product that — because Taiwan used to belong to Japan. So there were a lot of holdovers in Taiwan culture. So I just chose this name, Red Pine, and about three months later, I was doing some research on another book I was working on, and I discovered the first great Taoist in Chinese history was Master Red Pine. And said, wow, that’s important. And the more I began thinking about it, and this was when I was beginning to translate Cold Mountain, I began realizing that when you translate something, you — you are sort of a shaman. You’re at — you’re sort of an in between person. You’re not using your normal voice, you’re discovering a new voice. And so I just on a — on a whim, I said, well, I’m going to keep that for my translation name, because it explains a lot when I translate what happens, it’s red pine. It’s a red pine thing. And because my first books I — I could do this with. I self-published my first little chap book in Taiwan, and nobody asked me or said, oh, that that’s a — that’s a weird name, you can’t use that. So I just — just kept it. And when I published the Cold Mountain, they thought Red Pine was fine. It wasn’t until I was working like return to America, and I was working on the Diamond Sutra, and I’d signed a contract. Gary Snyder had introduced me to his publisher, Jack Shoemaker, at Counterpoint Press, and Jack was publishing my Diamond Sutra translation and commentaries, and he called me up one day and said, Bill, I’ve talked to my marketing people, and they say this Red Pine thing is just too — too new agey. It’s, uh, we gotta — we’ve got to get something that’ll help you sell the books. I said, well, Jack, if you think we can sell more copies, as with my books being by Bill Porter, that’s fine with me. And then two weeks later, he called me up. He says, I just talked to Gary. Gary says, you’re Red Pine. So — so my translation name has ever since been Red Pine, because, again, it’s reason I started using it was because it explained to me that this process of writing as a translator is different than writing out of my own head about my own life, my own interests. Because I’m a partner. Red Pine is a partner to somebody, a dance partner. David Devine: So I’m having this thought right now where you’re telling me you were, what was it, something cloud? Bill Porter: Yeah, victorious cloud. David Devine: So you’re a victorious cloud. And then you went to Red Pine. So you have this relationship of being up in the sky. And then you went to being a tree, to a pine tree. So you’re — you’re rooted, so you went from — from the heavens to the ground, and the translating is a conceptualization of bringing language together. So you’re bringing the heaven and the grounded earthiness all together in your translations. Bill Porter: Well, I never thought about that, David. But you know, what just occurred to me is — is that Master Red Pine was the rain master of the Yellow Emperor. David Devine: Yeah, and you’re the — Bill Porter: Exactly. So I that’s — that’s funny. So yeah, maybe that’s why I chose the name Red Pine when I did. David Devine: That’s awesome. I’ve heard a couple stories about the crazy master in the — the hills and the cloudy hills and all that. I listened to a lot of Terence McKenna stuff, and he talks about the guy up in the mountain in Cold Mountain poems and stuff. And it’s really interesting stuff. Bill Porter: Yeah, well, that’s why many people of that generation were attracted to Cold Mountain like Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder. A lot of the beats saw him as sort of their — a bodhisattva. He became the — he was sort of a guardian angel of the beat generation. I just ran into him by accident at this monastery in Taiwan. I’d heard about Cold Mountain, but suddenly the abbott gave me his poem, all of them right in my hand. I didn’t have to go research them or go look for them. They were right there. So I had this karmic connection with Cold Mountain. David Devine: Okay, so I want to get into this now. So you actually, recently were at Naropa. You were the special guest as the Lenz lecture. I think we do this like once a year or twice a year or something, but we sponsor a person to come and speak to the Naropa community, and you were the person this time around. And what I’m wondering is, can you explain to our audience a little bit about your experience of talking to the Naropa students and the community, and also, what did you talk about during your lecture? Bill Porter: Well, I didn’t really talk about anything. I decided I would read some poems, because that’s what I do, I translate poetry. But the poets I chose to talk about were — all had a relationship with the Dharma, because they told me one of the Lenz lecture has to deal with Buddhism in America. And so I thought, well, Buddhism in America means the dharma as Americans came to — to understand it. And of course, one of the first heroes of the American Buddhist movement was Cold Mountain. And so I read some Cold Mountain poems. And while I was translating Cold Mountain, I discovered another Buddhist poet named, Stonehouse. And so I read some Stonehouse poems. Stonehouse was a monk who lived around 1300 and he lived in a hut for 35 years on a mountain, and wrote these wonderful poems toward the end of his life. And so I translated them too. And so I read them. And then with all these — both Cold Mountain and — and stone house whenever they’re talking about their hero. In fact, anytime any Chinese poet of the past was talking about their hero, it was always the same person. Tao Yun Ming. Tao Yun Ming served as a young man — his family was well connected, and he served the two most powerful men in the kingdom as an aide, an assistant. And both of these men eventually killed the Emperor and became emperors themselves. And Tao Yuanming was 40, he finally said, I can’t do this anymore. And he got in his boat, he rode home, and he never left his home again. He spent the rest of his life as a farmer — farming, supporting him, himself and his family. Never worked again. Didn’t take money from people. He just tried to feed himself. And he lived a very, very hard life, but he wrote these wonderful poems that exemplify that decision. And so you see people like Cold Mountain quoting lines from Cold — from Tao Yuanming and Stonehouse the same thing. So the third poet I chose to — to read was Tao Yun Ming, because I just published his complete works last year. And finally, I will also read poems by somebody nobody in Boulder has heard of probably called (name?), poet who lived around the year 1200 who was the first person — first great poet in Chinese history, who was a general. When he was 20 years old, he cut people’s heads off and would bring the heads to the Emperor to show you know that they’d killed — he’d killed their enemies. So it was remarkable that — that eventually, uh, he switched to poetry when — when the Emperor asked him, these nomads took over northern China, and the emperor in his court had to flee down to South China, around Shanghai, they asked (name?) to come back down and help guard them, which he did, and then they kept him there. He always wanted to go back and fight the nomads, but the Emperor wouldn’t let him. So he started writing poetry. And it’s some of the most wonderful poetry I’d ever heard, and he — a lot of the poetry is — is with these — he writes — he was in monasteries from time to time, and has conversations with monks, and he became one of the great Neo Confucian thinkers of his time, too. So anyway, he was another poet I read. So I try to present four different voices — poetic voices that some of which American poets — American Buddhists have been familiar with, and some that represent the — what people have been thinking of. Because this last poet, (name?) his poetry is like jazz, completely different. All irregular lines. You never — sometimes a line is two syllables. Sometimes a line is…syllables because it was — it was composed, it’s called lyric poetry, poetry composed to music, but the music is gone. Nobody knows what the music was. All we have are the words he wrote to the music. You can imagine taking — take Bob Dylan’s, Blowing in the Wind, and changing the word, and then imagine having changed those words, we don’t know what the tune was. Nobody knows how Blowing in the Wind was sung — what the music is. So that’s where, (name?) poetry is like that. It’s all these — these words written to music, that the music is gone. It just the words of themselves you have to sort of find the music, but you have all these irregular lines. So as a translator, it’s like — it’s very much like going from classical music to jazz. David Devine: Yeah, that does seem a bit complicated to try and understand the artist who is writing the content and trying to translate it from a different language to another language, and then how you’re saying you don’t know what the tune is, and you’re trying to experience it, is there a cadence within the characters that are written that help you understand what the tune might be like? Bill Porter: Not — not me. I mean — I mean I can — I don’t read them that way, but I can — I know their pronunciation. And, yeah, it’s two syllables suddenly, then it’s five syllables, and I don’t pick up the music. I can’t get an idea of — and the Chinese have tried to reconstruct the music, but not very successfully. So even people who are Chinese can’t figure out what the original tunes were. David Devine: I see, interesting, okay. So one thing I noticed when I was watching your Lenz talk at Naropa, and you sort of just mentioned it a while back ago. You say you translate poetry, but you don’t write poetry. And that kind of struck me as interesting, because as someone who translates poetry, in my mind, I would think that you would kind of be thinking of your own sort of poetic display of words and flowing of ideas. But yeah, I was just kind of curious, is there a reason that you don’t write your own poetry, or is it just because you’re so involved with Chinese poetry and other people’s poetry that you just — you get your fill. Like, how does that work for you? Bill Porter: Well, I’ve never written poetry, and actually, I have — since becoming a translator, I have no desire to write my own poetry. Maybe you’re right, maybe I get my fill just as a translator. That’s so satisfying. I tell people it’s like this, I would never go on a dance floor by myself in front of other people. Never, I’d be too shy. And, of course, I don’t know how to dance. So it would be embarrassing for me to go on a dance floor and dance. And I don’t have anything to say either. I’m a translator. When I translate, I have something to say. I have a dance to dance. As long as there’s someone else dancing, I can dance with them. I love that experience of that, but I really don’t have — again, I have no desire to write poetry. There’s an American poet named William Merwin once told me, when he was young, going to, I think it was Princeton, he went to visit Ezra Pound, when Ezra Pound was held at the sanitarium in Washington, DC, St. Elizabeth’s. And he had asked Pound, what will be an important thing for him to focus in developing his poetic skills? And Pound said, learn to translate. So Merwin became a really great translator, but I’ve always thought it’s harder for a poet to translate than it is someone like me. I don’t have a poetic voice. I have nothing that gets in the way. I’d always imagine it must be hard for a poet to put aside that voice that they’ve developed and have a close relationship with this new voice that they’re hearing for the first time, David Devine: There’s almost like a want to, like, make the poem flow the way their minds thinking of it, because they have a poetic sense? Bill Porter: Right, because they’ve been publishing poetry, and they’ve developed a certain rhythm, certain ways of using language on the page and even the layout, how they’re going to write the line. And I don’t have that problem. I just, I meet a poet on the page and — and that’s — that’s what I’m doing. David Devine: Okay, I can feel that. It’s an interesting approach, too, because, yeah, just the thought of you have so much poetry going through your mind. I’m sure you think about poetry pretty often, and you think about other poets you’ve translated. But then I think the way my mind would work would be like, oh, I’d start making my own in my head. But I like the idea of what you just said, of how you meet the poet on the paper. That sounds very poetic in itself. There’s like a relationship building? Bill Porter: It is — it’s because — well, the Chinese, when they first defined poetry, it was called words from the heart. Poetry is words from the heart. So you’re — it’s not the words from the poet’s facial gesture or whatever. It’s from their heart. That’s what I love about Chinese poetry and to be a translator is to experience that. You really become intimate — really intimate, with these poets who lived a thousand years ago, you find they’re still alive. They’re not dead. Their heart is still beating in poetry. And that’s just a wonderful experience, and it’s hard to find any substitute for that. I’ve never thought writing my own poetry would satisfy me the way meeting these poets who lived a thousand years ago on the dance floor. David Devine: And also how their content is still relevant in today’s times, like doing good can never go out of style. Bill Porter: That’s true, and just expressing love and beauty. David Devine: Yeah, awesome. So I’m going to shift gears a little bit, because I know you did want to talk about this meditation hall that you’re starting. And so you told me that you recently started a non-denominational meditation hall called Camas Meditation Hall. And what I’m curious about is what inspired you to start a meditation hall and to have this community that you’re going to practice with? You know, because you’re coming from like a translator, Chinese text world, and then now you’re kind of moving it towards a meditation, community building aspiration. So I was wondering if you can speak on that? Bill Porter: Okay, yeah, sure. Um, well, it’s not so much that I started this, I came up with the, maybe an idea about doing this, and a friend of mine, who’s a carpenter, who also teaches Zen meditation here in Port Townsend, and I kept talking about we ought to, you know, build a meditation hall somewhere. And we — I tried several places, and we met some other people in the — in the town who had had a similar focus, some similar interests, and so as — as a group I’m part of, like a five or six member group, and we’ve been trying to instead of building a — we’re almost all Buddhists, but we decided that it would be better than just building a Buddhist place. We build a place that’s a community meditation hall, where people don’t feel excluded because they’re not Buddhists or Taoists or whatever. You don’t have to wear any special clothes or anything, they just come and sit. Because the thing I found about living in the monastery in Taiwan and sort of addictive too, just I almost hated to leave the monastery, because it’s so wonderful to practice with other people. It’s so hard to do that by yourself in your own living room, even when you have a small group, you meet once a week in somebody’s living room. That can — that’s still it’s like going to church on Sunday, and then what are you going to do Monday through Saturday? So anyway, we decided to try to get some land, which we did, and build a meditation hall. And we’re fortunate enough that one of the — our members knew this artist called, his name was James Terrell. He lives in Arizona, and he is an artist involved using light in space to create effects. And so we — we asked him if he would design our meditation hall. And also, when I first came up with this idea, I mentioned it at a poetry meeting in Port Townsend, the fellow next to — the city, next to me was a famous, well-known sculptor in Port Townsend. He said, if you guys built a meditation hall, I’ll make you a bell. And so he made us this 400 pound bronze bell. It turns out this this man, Tom J — this artist Tom J, was the college roommate of James Terrell when they both started studying art in — at Pomona College in 1965. And so Terrell remembered his old roommate, and so he agreed to design this incredible hall for us. And so we’ve finished the design now and we bought the land, and then we’re going to start raising money, probably beginning toward the end of this year, maybe early next year, if things don’t go well, but we’re going to try to begin around the end of the year and build this meditation hall. It’s going to be two floors, each floor, 3200 square feet modest slope. And the thing about it is, we bought this land in the middle of town. We bought four lots, 100 by 200 piece of land, so that we could create a meditation hall, not in the countryside, but in the middle of town, so that people could just stop in and think of — think of a meditation hall as a community swimming pool. As part of the community, a place you can just pop into to exercise, or in this case, to meditate, to de-exercise, learn how to let things go. David Devine: It’s amazing how much exercise meditation takes of trying not to think, like, trying not to think takes a lot of mental capacity. It’s wild. So, you know, you’re talking about like, there’s a bunch of people that are mainly Buddhist, I guess. But then you also have the non-denominational aspect of it. So what type of meditation will you be teaching your community when they come in, is it just kind of basic? Do you got some transcendental, you know? Is there, like Buddhist meditation? Is it guided? Is itself generated? You just kind of have a quiet space people sit. What does that look like? David Devine: Well, it’ll probably start with the idea of sit down and shut up, basically. But we’re going to have — we’re going to rely on volunteers for instruction. People will — who have — who’ve been practicing for a while, and they’ve all been practicing different things, maybe Transcendental Meditation, maybe inside meditation, maybe Buddhist Vipassana, maybe a Tibetan visualizations. And we’re going to let the — our community generate the kinds of meditation that are taught, and so that people get exposures in different kinds. And of course, there’ll be certain days of certain of the week when anybody who wants instruction in a certain kind can receive it. And we’ll be bringing in teachers of spiritual traditions. Like one person I asked to be one of our — one of our first people to teach meditation is the abbot of Gethsemane, the abbot of the — of the Trappist monastery in Kentucky where Thomas Merton used to live. So that we can teach Christian contemplation or Buddhist meditation, anybody who — who uses meditation in their practice, but that practice goes beyond meditation, you might say, with a spiritual component. And so we’ll have — we’ll be bringing in a — and teachers of those traditions too, but they — they won’t be people from our community, they’ll be — generally speaking, but we do have a lot of people who meditate — different ways of meditation here in Port Townsend, and so we’ll be relying on that — that resource to give people different exposure to different kinds of meditation, and then to that, adding periodic talks and visits by people who want to talk about the spiritual tradition that that meditation leads to. David Devine: That’s awesome. Like, I love the idea of providing the community with a mental workout space, a place to sit down and shut up, as you say, you know, because sometimes we need to shut up. We need, like a community to let us know, to shut up, in our mind and, you know, out loud. So it’s really beautiful that you’re going to provide a space for — and also not have, like a huge structure of meditation. You kind of go with what the community wants and what the community knows, and what people can bring in their offerings. So it’s really nice to hear that. Bill Porter: And this is something we’ve never tried, so we don’t know how it’s going to develop. We’re just going to create this place and let the community take it in some direction, because within 10 years, all of our board members are going to be dead, including me. So we’re not going to set it up so that it has to go in a certain direction. We’re trying to keep it open ended, so the people who decide they want to use this place can — can adjust it to their own interests and their own — their own perspective. David Devine: Yeah, you will not be dead. Your heart will still be beating alive in the community. You know, it’s like the hall is a representation of — of like your offering. So it’s really beautiful to have that. Bill Porter: We have a really wonderful architect doing the actual building. So it’s going to be a really amazing structure, and it should stand around for a while, but, you know, everything’s impermanent, but this is just something that I thought — I benefited so much from living in monasteries in Taiwan and in China, and the experience was so much — so beneficial to me. I’ve always wanted to share this with people, and I found a group of like minded people in Port Townsend. So we have a board of directors, and we have, we’re a nonprofit, and so forth, and we’re going to be raising money soon to build this place. David Devine: Yeah, I can’t wait to hear more about it. One thing I was thinking about when it comes to translating Chinese texts and poems, I’m wondering if there was a component of learning and reading and studying Chinese and poems that impacted your meditation. Was there a version in which learning the language, learning the — the people of those errors, speaking in their language and talking about the life of those times and their spirituality, did that inform your meditations when you were in the monastery and or like even now? Bill Porter: Not really, but — but I do use meditation to help with my translation work. When I do — when I read Buddha sutras, when I’m working on a Buddha sutra, I always having certain issues with certain lines, and I will use that line as a (?), as a (?), or a (?) that the subject of my meditation is that line. David Devine: It’s like a mantra. Bill Porter: Uh, exactly. I will just, I’ll meditate on that line. I’ll just put it in front of me, not on a page or anything, but in my mind, that line usually, it’s not — it’s only usually five or six, seven words, something like that, Chinese words, or Sanskrit words, usually Chinese words. So I’m just looking at that in my mind, and how am I going to deal with that? And without thinking about just putting it out there? Because when you translate, you run into walls, walls you can’t get through, and so you have to put that wall in front of you. And before you can — you can — before it just falls — falls apart of its, of itself. So I don’t use that with poetry so much, but my daily meditation, if I happen to be translating a Buddhist work and I’m having problems with the line, then that’s definitely going to be the subject of that — of my morning meditation is that line. And it’s amazing how successful that practice has become. It does really help to use meditation, the no mind mind, just looking at a line, without thinking about it, and then the line just falls apart. Amazing how — anyway, that’s my — that’s my trick. David Devine: When you say fall apart, what does that mean? Like you have your line and you think about it so much that it almost stops making sense, that it just distills itself back to sense, or like what does that mean? It means that you no longer see the Chinese characters, the words — just a crumble. And there’s — there’s something beyond the words that shine this, this light, you might say, shining behind the words, that suddenly the words are gone. But then this — this light is there, this idea that — what they mean is there. David Devine: Oh, I like that idea. I’m gonna play with that. Bill Porter: Because the reason, I meditated on this, is because the words are giving me a problem. I don’t know how to get through these words. David Devine: The words don’t exist, like I just see the light behind it. Bill Porter: Well, that’s true. You’re — it’s like, pulling the rug — the rug out from the words, and they just drop away and — and there’s, there’s something behind the words. David Devine: Okay, I really like this. So before we go, I’m wondering if you could just tell us a bit more about your meditation hall. Like, what are your plans? You said you’re gonna, like, start breaking ground. You’re gonna start raising money. Basically, can you tell the listeners and audience a website they can go to? Maybe they’re interested in helping, donating, being a part of. Bill Porter: Sure, yeah, we have a website. It’s camashall.org. Camas is C-A-M-A-S, Camas Hall, because our property has this plant on it. Camas is in the northwest — the Northwest Native Americans relied on Camas as their major source of starch. It’s like an underground potato tuber of some kind that grows on our property, and it’s an endangered plant in our area. So we decided to name our hall after it. So camashall.org is our website, and whenever we have news of what we’re doing, we will be putting it up on that platform, and there’s renditions of the hall itself that we’re building there, the architect’s pictures of it and the interior. We’re just finalizing the interior right now. We’re going to have, you know, two floors on a slope, so the — the basement, will actually be sort of like a daylight basement floor, and there’ll be a meditation hall on each floor, because we know this — this hall that’s being designed by James Terrell is going to attract a lot of attention. He’s — he’s world famous. He has many of his — his installations, his light installations, are in major museums in the in the world. So people are going to want to meditate in a hall like that. It should be an inspiring place to meditate. It’s a 40 by 40 hall with a 24 feet high walls and a 15 by 13 hole in the ceiling that lets the sky — sky into the hall. On the ground floor, though, we’re going to have another meditation hall for the hardcore meditators, who just — you know don’t need a hole in the — a hole in the ceiling to meditate. David Devine: It’s amazing how like beauty of light and nature and structure and architect can help you shut up and just meditate. Like being in those environments are conducive to calming the mind. Bill Porter: Yeah, I think so too. And I think it’s really good to do this, that we can afford to do this, where we think a lot of people in this town are going to be meditating for the first time. And so everything you can do to make that a more inspiring experience is going to help with their practice. I mean, it’s not like you really need anything, but it’s harder that way. It’s hard to get some help. And if the sky is a big sky space in the middle of the — of the roof helps, well, then so be it. But we’re going to also be using a Chinese — the Chinese meditation hall, or concept — we’re not going to sit on the floor. The average age of people in Port Townsend is over 55. So instead of — we’re going to use the perimeter platform. There’s a —usually it’s about a three foot wide bench that goes around the entire hall. So you — it’s usually about 17, 18, inches off the floor. So you can sit on the edge of the bench with your feet on the floor if you want. But you can also have cushions on this bench, because it’ll be about three feet deep, and then, you’ll cross your legs or just sit however you want to, in a comfortable way, because we’re not going to insist people have to sit in a lotus position. Just people find a way to be comfortable. David Devine: That’s awesome. Well, Bill, I really appreciate our talk. I really appreciate your knowledge that you have and you sharing with the Naropa community and the podcast and just your world of translating and how you see it and how you shared it with us today. And I really appreciate you coming on and speaking with us today. Bill Porter: Well, thank you for inviting me, David. I was really happy to spend a week at Naropa in Boulder. Great place. David Devine: Yeah, it kind of feels like there’s a lot of translating history. There’s a lot of Buddhism, sutra, spiritual poetry, history. You know, we have the — the disembodied poets at Naropa. So we have — we have a lot of history of writers and really awesome thinkers that come through. And so I’m just happy to have you be one of them to come through as well. Bill Porter: Well, I was really happy also to meet the embodied poets too when I was there. It was great to meet the people/ David Devine: Yeah, the ones that can write. Bill Porter: Well, there’s really a great — great community of faculties and staff, and just people in general in the community who come and live in Boulder. David Devine: Awesome. Well, thank you very much. Bill Porter: Okay, thank you David. [MUSIC] On behalf of the Naropa community, thank you for listening to Mindful U. The official podcast of Naropa University. Check us out at www.naropa.edu or follow us on social media for more updates.