by Candace Walworth PhD, Peace Studies Department Chair

“I found Naropa on the internet,” says Nayanne Abrantes Teixeria, who grew up in Brazil and transferred to Naropa in August from a women’s college in Missouri. “I was surprised to see that Naropa mentioned personal growth as part of the students’ journey. That was my hook to give it a try.”

As a Peace Studies major, Nayanne enrolled in my “Conflict Transformation: Theory and Practice” (PAX 340) class. In early September, we began exploring digital storytelling as a way to investigate the role of creative process in conflict transformation. We began with an ancient practice: sitting in a circle telling stories. We listened “inside” and “between” the stories for emerging futures that the storyteller was hungry for. We also grew more aware of the obstacles and rough patches we faced.

For instance, Nayanne’s initial sketches focused on the challenges of learning English, the journey of “daring to learn something that sounded so different, having a life here nothing like the one I had and missing every little part of it.” Another student wondered how to shape a story—an apparent coup erupting in his country of origin—unfolding in the present moment. Yet another student thoughtfully wrestled with questions of ethics and authenticity, as he found his role in telling a city’s story—the impact of gentrification on San Francisco. Some storytellers exposed too much too soon, as if attempting to climb an exposed rock face at Eldorado Canyon the first time out.

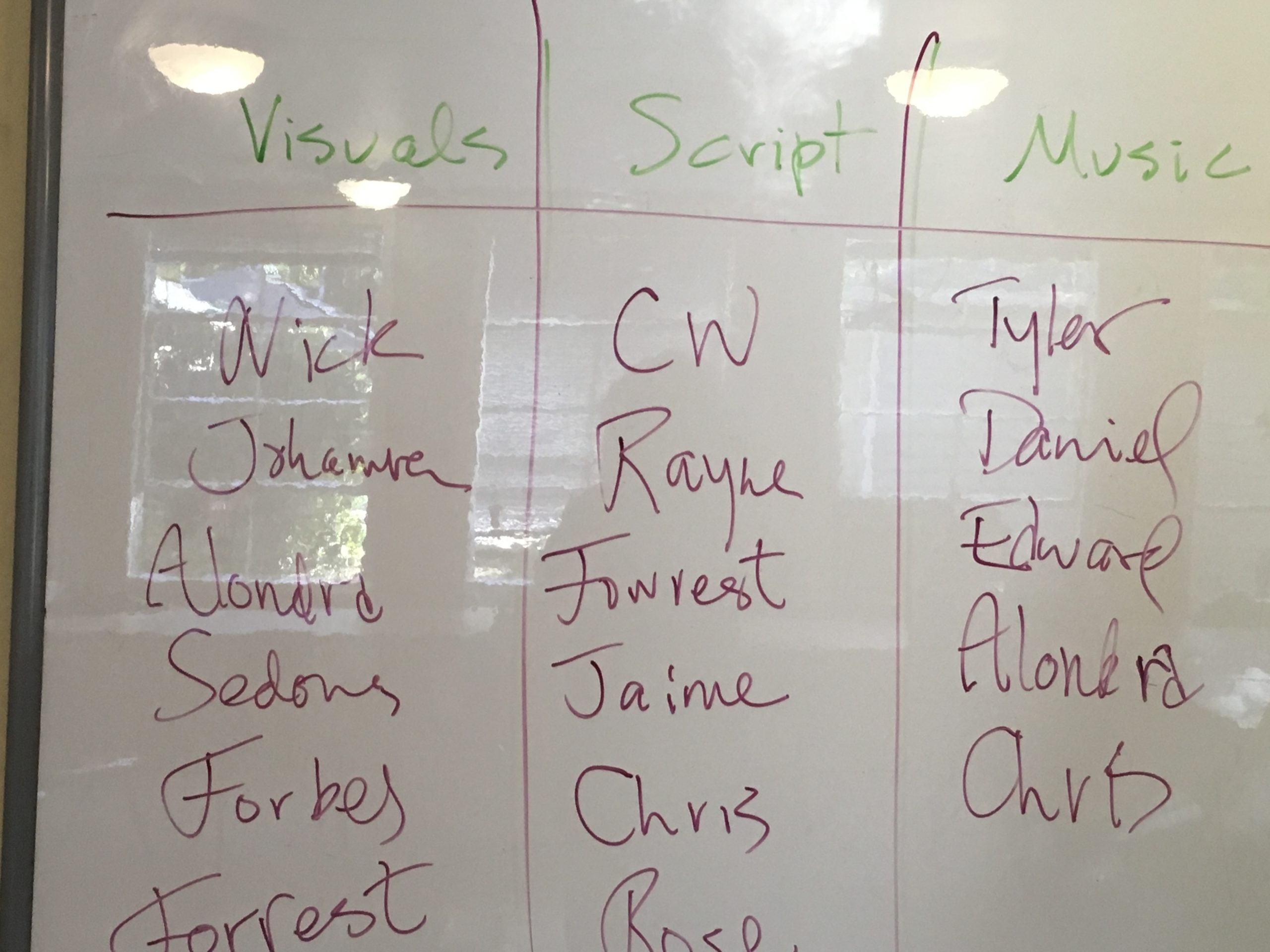

By the second week, we had identified our collective assets as a class—who to turn to when we had script-writing dilemmas, wanted feedback on image-selection or music, or needed video editing support and skills. So far, so good.

By the third week, however, most of us, including Nayanne, were tangled up in the mysteries of the creative process. As students grappled with finding and creating texts, images, and soundtracks for their stories, I wrestled with the messy and unpredictable dimensions of guiding multimodal community writing projects.

It wasn’t that teaching digital storytelling was new to me—last semester was my seventh time facilitating and mentoring digital storytelling projects in PAX 340. This time, however, several students struggled to—in Nayanne’s words—“find a story worth telling or interesting enough to share.” Why were students having trouble pinpointing stories, a process the StoryCenter refers to as “finding a moment of change?” Did they not value their own life experience?

Or was the work of finding a story intimately connected to the work determining how to tell a story? I was impressed by the methods with which students were experimenting, including recycling or up-cycling “old” stories or “quilting” together still and moving images, music, printed text, and spoken word to create new understandings of themselves and others. At the same time, I wondered if their experience of “finding moments of change” was getting lost as they explored ways in which to present their stories.

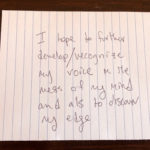

Drawing on an exercise I had learned from The Storytelling Project Curriculum: Learning about Race and Racism through Storytelling and the Arts, at the end of one class, I suggested the following: “Write two fears on one side of a notecard and a note about what you hope to learn from the project on the other side.”

These two notecards are representative of the responses I received:

Fears: “Not finding a story that I actually connect to. Not knowing how to express/build my story.”

Hope: “To further develop/recognize my voice in the mess of mind and also to discover my edge”

For several students, this exercise created a gap, interrupting loud and dismissive inner judges, making room for imaginative play. One student realized that she could compose and produce a non-linear story, experimenting with texture and mood, unraveling the notion of “story.” Another student decided that his story about his parents’ divorce, re-marriages and new blended families was worth telling even though many other “blended family” stories already existed. The story he wanted to tell had, at first, appeared to be off-limits, requiring that he listen for and to aspects of himself (and his parents) that had been muted during the divorce.

Based on a suggestion from a classmate, Nayanne experimented with composing and narrating her story (about boundary crossing and making friends with emotions) in Portuguese, her first language. While this was a promising start, her breakthrough came weeks later when she let go of alphabetic text as her starting point for composition. Instead, she began collecting photographs of people and places she loved, letting the images lead the process of discovery. With a cinematographer’s eye for juxtaposing black and white images with color, here is Nayanne’s digital story, which may evoke connections to your own learning journeys—whether inner or outer, whether on foot or by air across continents, cultures, and languages:

“When I opened to hear myself through the story, focusing on the narratives I carry inside, the story came into form,” Nayanne wrote in a final paper. “In my story, I could see how eager I am to be surprised by life—how I chase freshness of everything that surrounds me.”

Along with popcorn, the final class featured a film festival with short works by each of the fifteen members of the class. I opened the festival with a quote from A Traveling Jewish Theatre’s collaborative piece, Coming from a Great Distance.

“Stories move in circles. They don’t move in straight lines. So it helps if you listen in circles. There are stories inside stories and stories between stories, and finding your way through them is as easy and as hard as finding your way home. And part of the finding is the getting lost. And when you’re lost, you start to look around and to listen.”

Back row: Nyanne Abrantes Teixeira, Chris Teresi, Jodi Lefkowitz, Johanna Grube, Jahfaa Amadhi, Daniel Jubelier, Edward Galan, Tyler Dewey, Forbes Danckwerts, Alondra Kingman, Jaime Applegate.

Front row: Blake Gibbins, Candace Walworth, Rose Cowan, Forrest Gallagher, Sedona Allen.

For some students, the in-class film festival will be the only public showcase of their stories; for others, the project offers an opportunity to circulate their work to audiences beyond the classroom. Nayanne is among the latter.

![15107348_815627815245052_726775822190815255_n[1]](https://www.naropa.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/15107348_815627815245052_726775822190815255_n1.jpg)

Nayanne Abrantes Teixeiras hails from Goiânia, Goias, located in the central region of Brazil. She would love to continue writing and making short films.