Interview with Teresa Veramendi, Undergraduate Admissions Counselor at Naropa University

I hear that you are about to take a project about radical self-acceptance into some public high schools…tell me about the project.

This project is a collaboration between the Office for Inclusive Community and Undergraduate Admissions, with the goal of offering an entry point for any high school student into the power of contemplative practice.

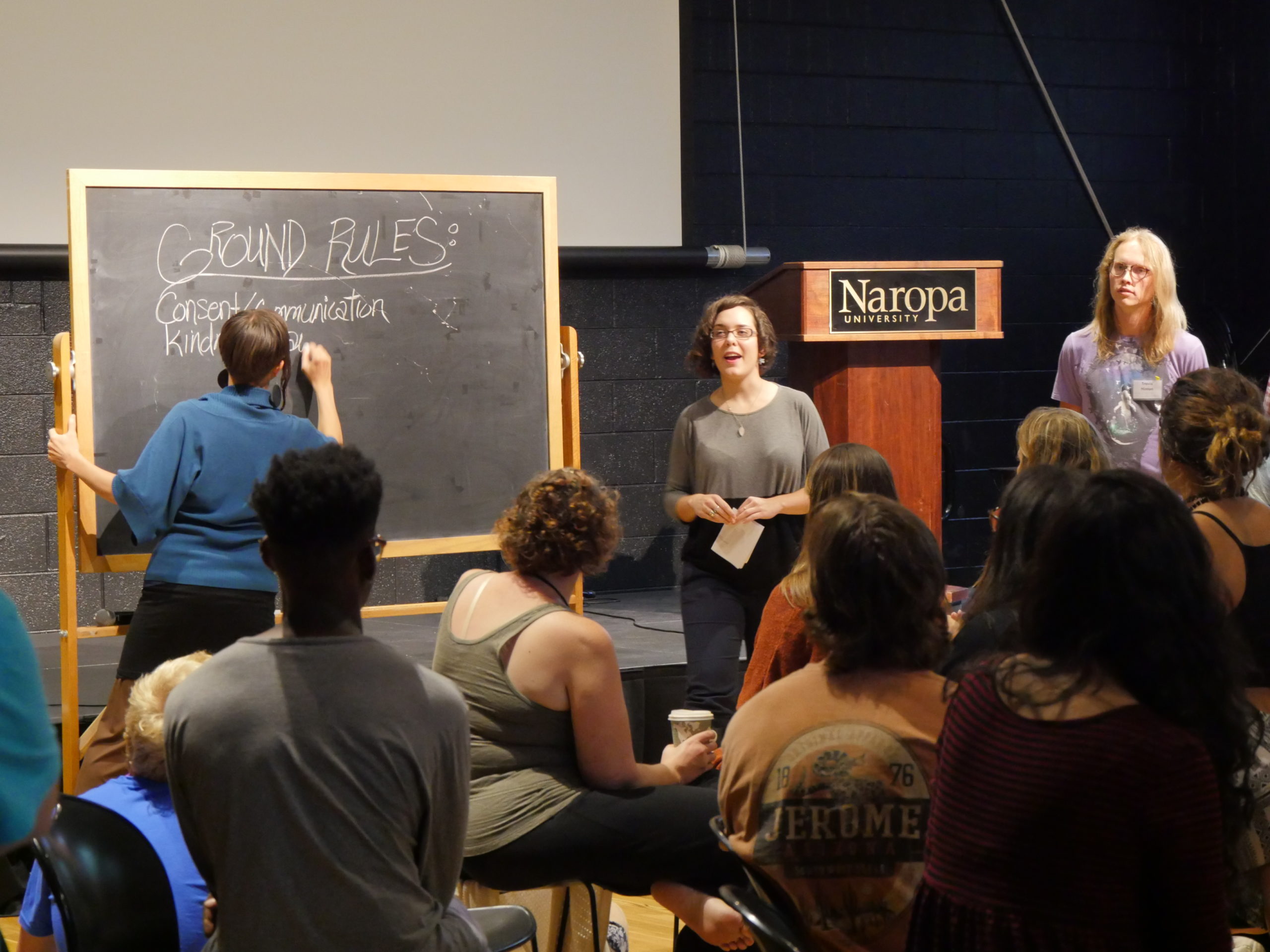

Regina Smith, my collaborator, is the director of the Office for Inclusive Community, and is an incredible facilitator of events and dialogues that empower all members of our community here at Naropa. I have been facilitating groups for several years using Theatre of the Oppressed as a way to open up discussions around power and oppression. It’s a technique that uses theatrical exercises as tools for embodied dialogue, and has been utilized with great success for decades all over the world.

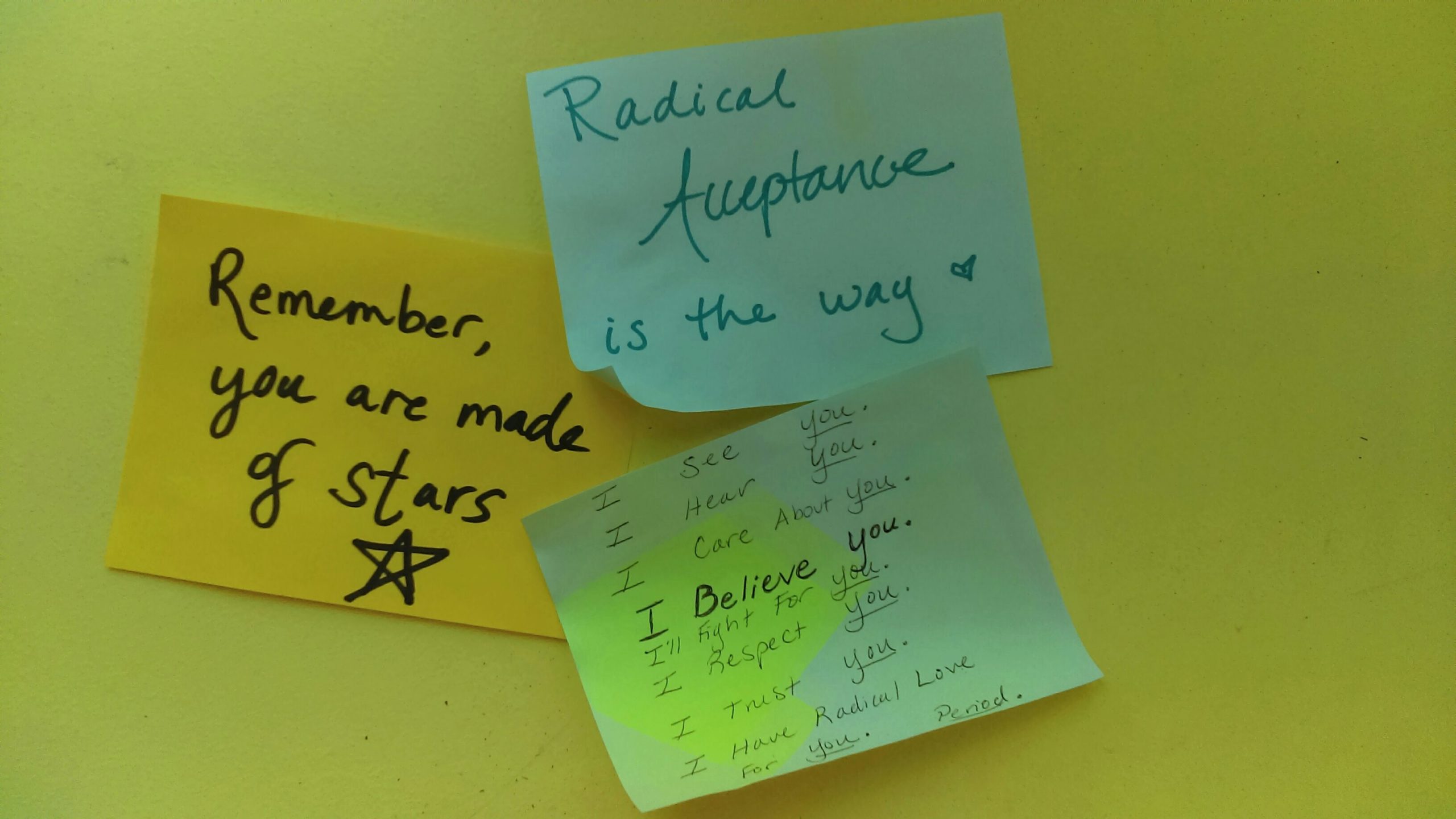

Together, Regina and I have created a new workshop called “Rewriting your story: A lesson in radical activism” to bring to high school students in Denver Public Schools. This workshop will empower students to examine their ideas about themselves, and embody the positive stories they want to own. This workshop series will also connect with a community art project begun by Naropa students called, “Love Notes to a Stranger.” We are altering this project a bit to become “Love Notes from a Stranger,” and high school students will have the opportunity to add an affirmation of their own to the project.

What was the impetus for this project?

We wanted to build a bridge between Denver public high school students and Naropa. As a graduate student at Naropa, I often remembered the youth I worked with in the underserved communities of Chicago. I wondered how meditation and mindfulness practices might alter the course of their lives, just as it did for me. Naropa is eager to connect with and support a more diverse student body, and in the past, we have not recruited many students from the Denver Public School system. We are aiming to reach out and change that.

How does this workshop connect to your work in undergraduate admissions at Naropa?

I often visit high schools in Colorado and other states to recruit young people for the contemplative education programs we offer at Naropa. Many students are surprised to hear that a place like Naropa exists, that we are fully accredited, and that we do have substantial financial aid support for our undergraduates.

By offering an interactive workshop, students can experience what our classrooms feel like through facilitated mindfulness and awareness practices. What’s particularly powerful about combining Regina’s background with mine is that we can guide students through a body-mind awareness practice, and then use the playful capacities of the body to feel into the stories students have about themselves.

We all have stories about ourselves. Some stories of self originate in other people, and can be self-defeating. What Eastern wisdom teaches us is that the mind is quite flexible. We can create new stories about the self, and if we practice them, they can become real. In this workshop, we are planning to do just that.

First, students will build their body-mind awareness. They take the time to feel their breath and state of mind. Then they play, open up the body, and feel what new story they want to believe about themselves. They feel the new story, play it out. They remember an old story, and feel the sensation in their bodies. What is the change in their body and mind? These kinds of self-actualization practices are the foundation of a Naropa education, and engaging with practice is one of the best ways to help students understand what it is we are offering.

This isn’t the first time that you have led workshops in high schools, is it?

No, I have done different kinds of work in high schools. I worked for a youth empowerment program in Chicago, and during the school year I visited health classes and used community theatre to open up discussions with young people about pregnancy prevention. Students would write and perform a scene where a young woman tells her boyfriend that she is not ready to have sex. We’d use theatre to identify what consent really looks like – and this was very powerful for the young women in those classes.

It’s very potent cultural work that theatre can do, particularly once it’s taken out of the context of spectacle, talent, and fame. Because when we see someone cry, the same parts of our brain light up, as if we were crying. These are called mirror neurons, and they are the root of empathy. This is why I am so passionate about the power of theatre to shift culture. Put that power in the hands of our youth, and amazing things can happen. I’ve learned so much by giving young people power over the script and stage in a low-pressure, community-oriented environment.

Has studying mindfulness at Naropa affected your work as a facilitator?

Since graduating from Naropa, I have noticed a number of shifts in how I facilitate community workshops. For one, I am less in a rush to push through the activities I’ve prepared, or to get to a kind of “solution.” In the past, I would feel the pressure of satisfying the participants of the workshop, and I would somewhat unconsciously nudge the workshop towards an answer I believed was right. Now, I allow the group to manifest their journey organically that day.

I recognize that the process of asking difficult questions about privilege, oppression, and allyship is the purpose of my work. Facilitators don’t answer these difficult questions, instead we provide a safer space where participants can grapple authentically with their questions and find their own solutions. I have never attended or facilitated a workshop that didn’t stay with me afterwards, that didn’t continue questioning the situations and behaviors that arise in my life.

I’ve learned to trust this, to trust the wisdom in the room. And I’ve also learned to honor the emotional vulnerability that can arise. While tears might have struck fear in me as a young facilitator, now I recognize the opening that has occurred in the field of the room. I create time for participants to feel the emotions that arise, to breathe and feel the earth supporting them. I create time for participants to be in authentic presence with themselves, and to sense if they are ready to share a particular story with this group on this day. These new practices emerged naturally from my training at Naropa.

Now that I am more in touch with my own body, mind, and emotions, I recognize the importance of facilitating that for others while we talk about how to change the world.

What do you hope students will gain from this workshop?

I hope students will connect to their personal power, and see that they have control over their outlook. As a young person, I often felt helpless, and I think many young people do. They are old enough to feel the impacts of the cultures we have built, but not yet old enough to be widely respected for their opinions and suggestions. Teenagers are old enough to go to war, but not old enough to vote and be heard by our government. Young people absorb everything, and are in the process of discerning what ideas to keep and what ideas to throw away. This workshop empowers them to begin by choosing their story of self, and to fully feel it in their bodies and minds. My hope is that it opens an avenue of possibility for them, that they can change their mind, and thus change their lives.