by Johanna Grube, 2nd year Mindfulness-Based Transpersonal Counseling Clinical Mental Health Counseling student

by Johanna Grube, 2nd year Mindfulness-Based Transpersonal Counseling Clinical Mental Health Counseling student

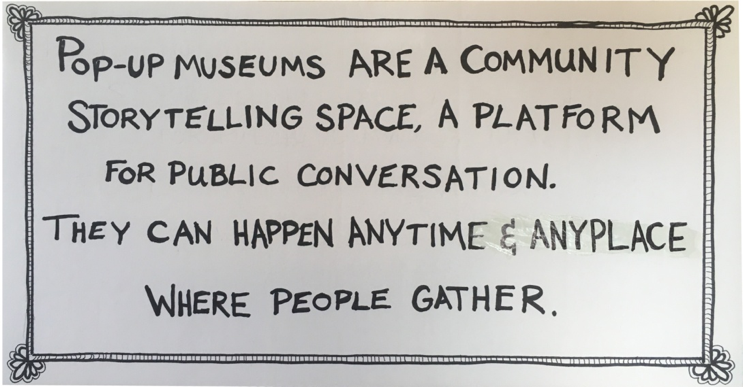

Candace Walworth‘s “Socially Engaged Spirituality” class hosted a Pop-Up Community Museum in the second week of classes. The format was new to Candace, and as the Peace Studies Graduate Assistant, I had the opportunity to brainstorm with her in the weeks prior about how best to adapt the structure to function as the first class project.

I began my undergraduate college career as a photography major at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and finished with a Bachelor of Science in Visual Studies from the State University of New York at New Paltz. Both my education and family history have steeped me in a critical, academic approach to art. From this environment, I understood that the primary value of contemplative practice was its ability to enrich an individual’s output (deeper, more complex, more interesting pieces of art, writing, and analysis). The idea of a Pop-up Community Museum, focusing on the theme of ‘Intersections’ was exciting to me. I imagined it as an opportunity for students to present engaging and provocative commentary, through physical artifacts, to a community audience. However, as the event drew nearer, it became clear that my orientation to the project was missing the point.

“It’s not about the objects; it’s about the stories,” Candace said in one of our meetings.

It was an offhand remark, made in the context of a larger discussion about facilitating a co-creative learning space. However, the simplicity and directness of the statement stuck with me.

Art school required a sustained attention to the development of my own aesthetic, to my own conceptualization of the source, meaning, and function of art in all its forms. However, there was barely any explicit acknowledgment of the need to nurture that development – and so, I and most people I knew cobbled together intensely personal practices to meet the demands of our education. My first experience with formal contemplative practice, a 10-day Vipassana course, felt like coming home. Suddenly there were words to describe what I had been doing – there was a whole community I could converse with.

My relationship to art is what lead me to the Mindfulness-Based Transpersonal Clinical Mental Health Counseling (MBTC) program here at Naropa. The fields might sound disparate, but for me, art has always been about creating and searching after reflections of what it means to be human, about finding and facilitating a deep sense of belonging in this world. As I’ve begun to apply these interests to the format of the therapeutic relationship, I realize that there has always been something isolated about the way I relate to art and creativity. The art of others reaches me as a correspondence, a letter that I open alone.

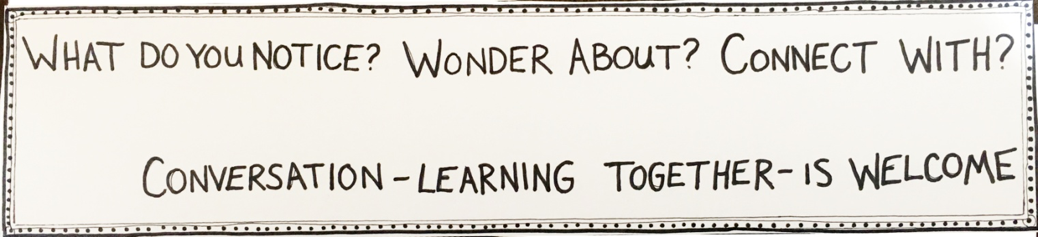

Now more than halfway through the MBTC program, it seems that fundamentally, we are being taught to apply the skills of contemplative practice to an interpersonal, relational context. Contemplative practice asks us to devote our attention to the present moment – a moment that will always be unknown. We are asked, not only to inhabit this uncertainty and abide with whatever we find there, but to do so with an attitude of loving-kindness. These qualities are precisely what make a relationship therapeutic, they are qualities which function interpersonally to foster empowerment and growth.

The value of a contemplative approach to relationship is obviously not lost on Candace, and the more I work with her, the more her methods surprise, frustrate, and ultimately demonstrate what contemplative relatedness might look like.

It’s not about the objects, it’s about the stories.

Or perhaps, better to say ‘StoryWork’ in order to differentiate between stories as objects which might communicate a fixed message, and stories as an active method of connecting, a method of creating space for discovery. Even as Candace’s assignments include narrative products, it seems that the point is the practice of stepping into the unknown together – as a community.

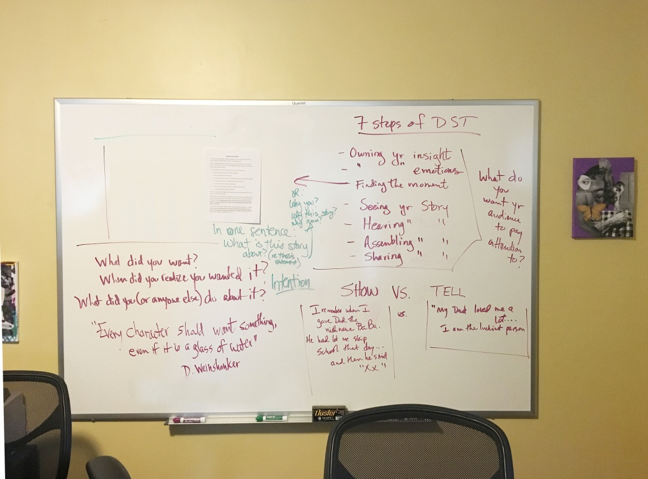

Last fall, students in the “Conflict Transformation” course were given a challenge in their first class:

“Tell a story you’re hungry for, that only you can tell.”

This directive does two things. It asks students to find their own voices, and to open themselves to the experience of longing to find a story not yet formulated within them. It asks students to find themselves as they are and to share that self with their community.

At the end of that first class, we stood in a circle. I remember Candace saying, “I’m going to guess that by the end of the semester, you will be able to look around the room, and note each classmate’s contribution to your learning and creative work — perhaps this person blowing the whole thing apart with a question, another offering an out-of-the-box synthesis and yet another playing the mandolin for your story.”

I think it was a good guess.

What you don’t see in the digital stories that came out of this project is the importance of that collaboration, not as a byproduct, but a primary result of the process. You can’t see the group cohesion that was building as each student shared iterations of their story and responded to their classmates’ stories. You don’t see the altruism that blossomed as students met their peers’ difficulties with empathy and volunteered their own wisdom and skills to support one another. You don’t see the way that one student’s change in perspective helped others reframe their own stories in powerful ways.

Perhaps you can hear the echo of those things.

By Jahfaa Amadhi and Daniel Jubelirer, here are two digital stories from fall 2017’s Conflict Transformation class.

Jahfaa Amadhi, originally from Hershey, Pennsylvania, will graduate in May 2018 with a degree in Interdisciplinary Studies. His concentrations are in Somatic Psychology, Peace Studies, and Performance. His thesis will be an autoethnography exploring how culture perpetuates toxic expressions of masculinity.

Daniel Jubelirer longs for a world where we all belong. With East Coast roots in North Carolina, and West Coast fruits in the Bay Area of California, Daniel graduated with a BA in Peace Studies in December 2017. As a community organizer, youth educator, artist, facilitator, and activist he follows a passion for linking personal, interpersonal, and systemic change in the building of a radically just and beautiful world.

Johanna Grube is a 2nd-year student in the Mindfulness-Based Transpersonal Counseling Clinical Mental Health Counseling program. She combines a background in visual art and social justice activism, with her academic training and experience with diverse clientele to promote health and well-being through therapeutic skills which are creative, client-centered, and mindfulness-based.

Johanna Grube is a 2nd-year student in the Mindfulness-Based Transpersonal Counseling Clinical Mental Health Counseling program. She combines a background in visual art and social justice activism, with her academic training and experience with diverse clientele to promote health and well-being through therapeutic skills which are creative, client-centered, and mindfulness-based.