As Naropa University celebrates its 50th anniversary in 2024, the cultural conversation surrounding psychedelics is once again at the forefront of societal discourse. Interestingly, this resurgence mirrors the cultural climate of Naropa’s founding in 1974, when psychedelics permeated the zeitgeist, albeit with a different flavor.

In the early 1970s, psychedelic use encompassed a spectrum of motivations beyond mere recreation, including cultural, philosophical, exploratory, and sacramental purposes. While there were a few endeavors like the Harvard Psilocybin Project that acknowledged the therapeutic importance of integration and psychological wellbeing with psychedelic use, the American counterculture using these substances largely lacked a coherent, structured framework to process their profound experiences. A significant number of faculty and students who were seeking guidance and concrete methods for enacting the transformative changes they had glimpsed through psychedelic use were attracted to the founding summer of 1974.

Anne Waldman, experimental “Outrider” poet, close collaborator of the beat poets, poet, and co-founder of the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa, says that she found herself turning to Buddhism as a frame to contain and hold her experiences with psychedelic use. She explains, “My first LSD experience was a partial blueprint or paradigm for the actions and karma of my life so far…The inspiration from that first vision—and its fantastic and historic milieu—did much to forge my commitment to sangha, community, both Buddhist and poetic.”

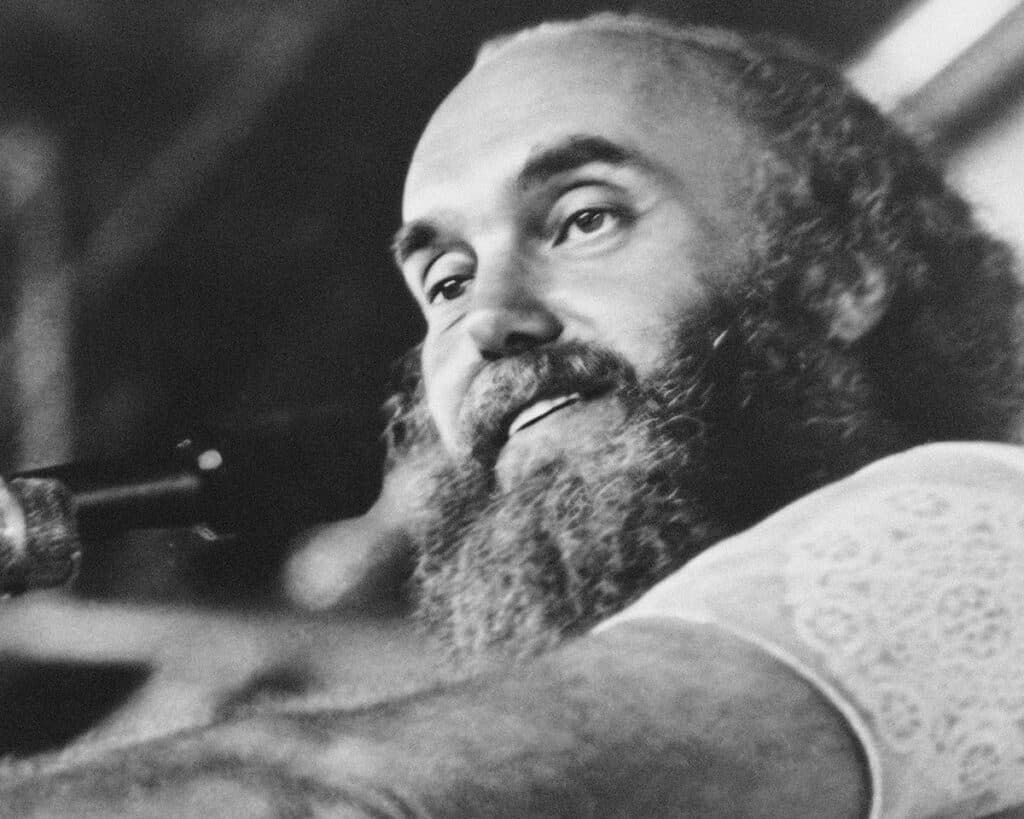

Waldman wasn’t alone in this experience—her friend and fellow poet Allen Ginsberg had been experimenting with mushrooms at Harvard alongside Timothy Leary, an experience that significantly influenced Leary’s trajectory, as documented in The White Hand Society by Peter Conners. Ginsberg, like many of his contemporaries, found Buddhism to offer a fitting language to articulate his psychedelic experiences. So it is not surprising that when an exiled Tibetan Buddhist monk established an experimental school rooted in Buddhist principles, figures such as Waldman, Ginsberg, and Ram Dass were drawn there—not solely by their psychedelic experiences but by a broader quest for spiritual and creative exploration.

Andrew Schelling, Naropa faculty and longtime community member, says for some, the school served as a place for “refugees from their psychedelic travels,” individuals in search of practices and disciplines that could provide grounding and direction. This period saw a turn towards contemplative disciplines, the arts, back-to-the-land movements, and other practices that could complement and enhance the insights many early attendees may have gained from psychedelics. In this way, Naropa University absorbed the energy and spirit of the psychedelic era and sought to construct an institution grounded in the integration of wisdom and knowledge of the East and West, emphasizing social transformation and personal insight as core principles.

It is important to note that while Naropa absorbed this psychedelic energy, it did not necessarily mean that the casual use of psychedelics was condoned. Naropa’s founder, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, was sympathetic toward his students’ psychedelic use but ultimately advocated for a more direct, sober approach to the exploration of one’s consciousness. Ginsberg explains Trungpa thought psychedelics were “too trippy, whereas people need to be grounded [because] everything is uncertain enough as it is…What’s needed is some non-apocalyptic, non-ambitious, non-spiritually materialistic, grounded sanity, for which he proposes shamatha meditation discourages grass and acid, which is logically sensible.”

Similarly, the late Naropa graduate Jim Jobson remembered Trungpa saying in a lecture in the fall of 1973 that “taking LSD is like driving a car to go next door. It’s better just to walk, and then you see what’s on the landscape.”

Trungpa was clearly not sold on psychedelic use as a substitute for spiritual practice but was still open to discourse about its utility in an academic setting. President Charles G. Lief explains that ultimately, “Trungpa Rinpoche made a big distinction between frivolous use of the medicines and disciplined use, which of course was more limited in the ’70s and ‘80s. But the reason we invited Stanislav Grof, PhD, and his then-wife Joan Halifax as first-year faculty at Naropa was because of their careful work with LSD at the Maryland Psychedelic Research Center. The same holds for welcoming the noted Chilean neuro-biologist Francisco Varela, PhD. A student of Trungpa Rinpoche, Varela’s groundbreaking work on neurophenomenology created the road map for the rigorous study of consciousness that both framed the many clinical trials with psychedelics and was also the foundation of the Mind and Life Institute, co-created by Varela, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and Boulder-based Adam Engle. This was the fertile ground which was Naropa from the beginning.

While its early years saw an influx of individuals seeking to integrate and better understand their experiences, Naropa’s commitment to groundedness and disciplined practice, as advocated by its founder, laid the foundation for a nuanced approach to psychedelics. Through the uncontained or undisciplined use of psychedelics within the Naropa community and beyond, important lessons were learned about the importance of ‘set and setting,’ the delicate interplay between one’s internal state and the external environment during a psychedelic journey. These early encounters highlighted the critical role of safety, not as a restrictive measure, but as a foundation for maximizing the transformative potential of these powerful substances.

For Naropa and other institutions who are interested in psychedelics, I think we have an enormous responsibility to roll this out in a safe way that is maybe a bit slower than some might like, but I think that that’s better to set the groundwork and create a good and safe container.

Following decades of suppression, the recent resurgence in science and research has demonstrated promising results for the use of psychedelic substances in the treatment of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), end-of-life anxiety, addiction, and other mental health conditions. As a pioneer in the integration of contemplative training with counseling psychology, chaplaincy, ecopsychology, and other therapeutic disciplines, Naropa is uniquely positioned to expand the healing potential within this emerging field.

Even before the recent string of legislation legalizing the use of psychedelics in a clinical context, Carla Clements, PhD, former faculty and chair of Naropa’s Transpersonal Psychology Department, played a pivotal role in laying the foundation for this type of work. Clements found transpersonal psychology to be the “only field that allowed for the possibility” of studying alternate states of consciousness, and her time at Naropa expanded her interest in how psychedelics could aid patients in a therapeutic setting. Since retiring from Naropa in 2018, Clements has continued her research independently, notably as the Principal Investigator of the DMTx program, exploring the therapeutic potential of DMT. Her deep understanding of transpersonal psychology and her dedication to expanding the field have greatly influenced the trajectory of psychedelic studies.

Building on this work, in 2020, Naropa launched its first post-graduate clinical training in psychedelic-assisted therapy. The eight-month program includes a module focused on MDMA-Assisted Therapy in collaboration with MAPS PBC, now Lykos Therapeutics. MAPS conducted a number of FDA clinical trials using MDMA as a possible therapeutic for PTSD. The largest of those trials took place in Boulder. The lead trainer, Marcela Ot’alora and Principal Investigator for the Boulder MDMA-Assisted Therapy clinical trials, herself a Naropa alumna (‘99), had long wanted to bring psychedelic therapy back to her alma mater. The Center for Psychedelic Studies was formally established in 2021 with the support of faculty members including Sara Lewis, PhD, and Jamie Beachy, PhD. The Center then attracted Diana Quinn, ND, and Victor Cabral, to round out the leadership team under the direction of Joseph Harrison following a 20-year career at Johns Hopkins. Recognizing the growing importance of psychedelics within a structured and ethical framework, Naropa joins a cohort of pioneering institutions such as Johns Hopkins, UC Berkeley, Columbia University, and the California Institute of Integral Studies that have been at the forefront of psychedelic research and education. Through the Center, Naropa fosters the development and integration of psychedelic studies throughout the university while also providing various public education opportunities.

Sara Lewis, who serves as Director of Training and Research for the Center, says, “For Naropa and other institutions who are interested in psychedelics, I think we have an enormous responsibility to roll this out in a safe way that is maybe a bit slower than some might like, but I think that that’s better to set the groundwork and create a good and safe container.”

Lewis emphasizes, “Psychedelics are not for everyone at every time in their life. That presents a good question of how might someone know if it’s the right time for them to begin using psychedelics. That is a big part of our clinical training—to train the therapists and chaplains coming out of our program to not be opening the doors and taking anyone to begin this therapy, but working through a screening process.” This commitment to responsible use and thorough assessment forms the cornerstone of Naropa’s approach, ensuring the safety and wellbeing of individuals seeking psychedelic therapy.

Naropa’s commitment to safety also extends beyond screening and training. As Lief states, “A clinical practitioner has to be able to hold the space and to be able to support that patient in the journey they are taking together. That can actually be trained—we can teach people how to know their own minds, to understand how to make space and time very elastic, to be humble, and to drop their preconceptions—those are completely learnable.”

Naropa’s Center for Psychedelics Studies is teaching these skills through two training programs for individuals interested in becoming psychedelic facilitators. The Center’s flagship training program, the Certificate in Psychedelic-Assisted Therapies (CPAT), is an eight-month, 150-hour, non-degree certificate program that provides postgraduate level training for advanced professionals working in relevant therapeutic areas including mental health counseling, psychology, medicine, chaplaincy, and social work. The Center also recently announced a Certificate in Psilocybin Facilitator Training (PFT), a six-month virtual learning program for individuals interested in becoming psilocybin facilitators. The PFT is accredited by Oregon and Colorado, the two states where psilocybin use both therapeutically and spiritually is now legal. This year, they expect to enroll approximately 200 facilitator trainees in their CPAT and PFT certificate programs.

There is tremendous wisdom from the indigenous communities, and there is tremendous concern in these indigenous communities about having their medicine and healing spiritual heritage appropriated by those that are not part of that community. Our obligation is to make sure that we are both allies of those communities and that we do everything we can to learn from them.

Director of the Center, Joe Harrison, explains, “I see the Center’s future-forward mission as being to create quality educational opportunities for our undergraduate and graduate students, to train this new generation of psychedelic facilitators, and to create a space for both clinical research in and therapeutic delivery of psychedelics when legal to do so.”

In the fall of 2024, Naropa began offering a minor in Psychedelic Studies for undergraduates with an interdisciplinary emphasis in the humanities and social sciences. Looking towards the future, in the fall of 2025, Naropa will launch a concentration in the Master of Divinity program allowing students to train in the burgeoning field of psychedelic chaplaincy. The Center intends to open a clinic in Boulder in the coming years, which will support clinical trial research, internship, and practicum opportunities and will provide affordable psychedelic care for the local community. Given the complexity of an emerging field where federal and state policy and laws are evolving, the Center is working on creating a standalone entity with an independent legal structure while remaining closely aligned with the university. A key differentiator of the Center’s work is the integration of anti-oppression work and indigenous wisdom. This includes educating students about the historical harms of colonial extraction and appropriation related to sacred plant medicines, fostering respectful relationships with indigenous communities, and understanding the ethics of cultural appropriation.

Lief explains, “We need to understand that there is tremendous wisdom from the indigenous communities, and there is tremendous concern in these indigenous communities about having their medicine and healing spiritual heritage appropriated by those that are not part of that community. Our obligation in that case is to make sure that we are both allies of those communities and that we do everything we can to learn from them.”

Beyond cultural sensitivity and respect for indigenous traditions, Naropa also recognizes the vital need for equitable access to psychedelic therapies. This goes beyond mere inclusion and delves into systemic change. Ensuring that the benefits of psychedelics reach beyond the privileged few requires addressing systemic barriers. By advocating for a more distributed model, Naropa acknowledges the limitations of the current medical system and seeks innovative solutions that prioritize accessibility and affordability. This approach aligns with the institution’s commitment to social transformation and ensures that the healing potential of psychedelics reaches those who need them most.

Expanding training opportunities for diverse practitioners and exploring alternative models that move beyond traditional doctor-patient ratios are crucial steps. To that end, the Center has a robust scholarship program awarding over $100,000 in scholarships in 2023 to trainees in the BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ communities, which they doubled in 2024. The Center awarded full-ride scholarships to indigenous clinicians from federally recognized tribes.

Lief emphasizes that “every single one of us can share in this work,” whether through direct involvement, policy advocacy, or simply supporting the reunification of the sacred and the scientific.

“It’s really only been in the last 200 years that the science of medicine and the mystery of the spiritual experience have separated. Before that, there was an easy movement between what we meant by spirituality and what we meant by mind-body healing…it was an integrated whole, and now there’s an opportunity for this to come back together.”

At Naropa’s 50th anniversary, it stands at the nexus of an important cultural revival, reminiscent of the era that birthed its unique ethos. Through its countercultural lineage, dedication to consciousness exploration, and commitment to social justice, Naropa has not only embraced the legacy of psychedelics but has also pioneered a path toward responsible integration within therapeutic frameworks. As we navigate this renaissance, guided by principles of safety, equity, and reverence for indigenous wisdom, Naropa remains steadfast in its adherence to reuniting the realms of science and spirituality for the betterment of humanity.