A year after I arrived at Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School, Hakim Bey published Temporary Autonomous Zone. The book had two subtitles, “Ontological Anarchy” and “Poetic Terrorism.” The mix of slightly obscure revolutionary rhetoric, with its promise for poetry, gripped everyone. Anne Waldman, who founded the Summer Writing Program, began to refer to the grounds and its writers as a temporary autonomous zone. Then most of us picked up the term: TAZ for short. Temporary—or should you adjust your lens slightly—Disembodied—since a large white tent went up on the green, and four weeks later came down. In the interim, 150 people would meet, talk, read poems, discuss ideas, argue about love and politics, and write. Though my memory is pretty good, I can never quite think back and recall who signed up as students, who had been summoned as guest faculty, and who showed up simply because aside from the Mongolian camel festival, it was the best place to be for four weeks of the year.

Bey’s idea seemed immediate and obvious. In the late twentieth century, any zone of freedom dedicated to love, wisdom, independent thought, or good art, would quickly be found out. Predatory business interests would move in, a police force, or simply hangers-on who came for the feast but wouldn’t offer in return the hard work of revolution. We had better get used to the idea that the zone—this Summer Writing Program tent—was temporary. When the dismantlers arrived, we’d melt into the countryside like Castro’s or Che Guevara’s forces.

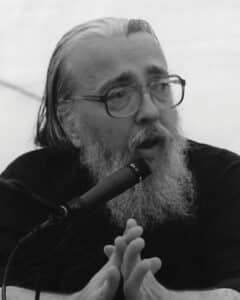

Bey published under another name, too: Peter Lamborn Wilson. We called him Lamborn. I surmised that the name Hakim Bey was for his standing in some Sufi order. No, he said; he’d once made his living writing pornography and figured a pen name might keep him a step ahead of the police. The Zone might last a few days longer.

Along with Lamborn, others came to Naropa for the full four weeks of the summer program. Guest faculty stayed in a block of cheap University of Colorado apartments. Allen Ginsberg stayed longer, sometimes another month, since he, Waldman, and myself had a lot of work to do; figuring out future plans for the program, drawing up lists of prospective guest faculty, adjusting calendars and budgets. Ginsberg wanted to cook his own macrobiotic food—he had late-onset diabetes pretty bad—so he simmered pots of rice and cauldrons of vegetables in his quarters. Singer-guitarist Steven Taylor and poet Lee Ann Brown would come for the month, bringing what they called their anti-nuclear family. This included other poets, members of Taylor’s punk band The False Prophets, and a changing ensemble of smart, dark, inward youngsters in leather jackets. I never figured out who they all were. Some seemed runaways, some lovers, some children. Or maybe just more weird band members.

Group events took place under the big white tent. In good weather the canvas sidings stayed up; in inclement we’d roll the flaps down. Talks, lectures, symposia, panels, presentations. (Nighttime formal readings happened in the Performing Arts Center.) The tent sat on Naropa’s green. In those days, no library to hedge things in, no fence to seal off the grassy area from university parkland. Our grounds stretched without obstacle to the massive cottonwoods and acres of irrigated lawn, out to where sports fields ended the Zone. When Lamborn lectured—it could be on money, magic, open love communities, Islamic heresies, the Romanian revolution, or mushrooms in Irish mythology—one or two VW buses would pull into the parking lot. Colorfully clad men with beards and longhaired women would file quietly into the tent and sit at Lamborn’s feet. When he finished they trooped out, got into their buses, and drove off as mysteriously as they had arrived.

To step into the cosmic scholar cottage was to enter a subterranean warren. Some stinky old wood rat lived here, an ignoble-looking creature that turned out (once you passed the impossible test) to be a spirit animal.

At the west end of Naropa’s Arapahoe Avenue campus sit seven misshapen clapboard or stucco-walled outlier buildings: former chicken coops, livestock barns, or tool sheds. In them, during the 1980s and ‘90s, the Institute housed faculty and students. Inside one dwelled Harry Smith. How many people have listened to, been influenced by, or at least heard tell of his six-disk 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music, from which the rock musicians of the sixties learned their American vernacular fare? People who never heard of Smith know the songs he compiled by heart. Accounts of Smith sometimes note that he lived during his final three years at Naropa. The recent biography of Smith, by John Szwed, calls him “Cosmic Scholar.” He was a filmmaker, poet, occultist, soothsayer, archivist, and early tape loop artist. His quarters were two rooms, cramped and dark. I remember a lot of cats. Daylight got in through small windows that backed up against other buildings. When the weather was good, he kept his south-facing door ajar.

Smith had amassed a library that stuffed the rooms. The late Dick Schwartz of Stage House Books provided him with a perhaps boundless credit line. Anthropology, linguistics, philosophy, psychedelics, titles in piles and stacks, in kitchen cabinets, in the bathroom, among notepads, cat food tins, musical instruments, and among a many-decades-in-the-making collection of paper airplanes. Now that Schwartz is gone, there’s nobody to ask if his bill for all the books got paid. The bookstore, which once fed impecunious Smith, is now a restaurant that serves costly, ornate food to young warrior-wizards of the tech industry.

As the twentieth century recedes, it’s worth pausing a moment to reflect. Just a few decades ago the US economy, the pressures on a small experimental college, the Federal oversight committees, and a different sense of community, were loose enough that a person of scant means and questionable status could be housed on a degree-granting university campus with no known duties. No academic credentials, no paycheck, no health care, no worry about budgets. Smith’s job seemed to be to carry out baffling conversations or draw down bolts of lightning. Nobody checked his portfolio, but he adopted a position something akin to “resident cosmonaut.” He wandered the streets of Boulder pursuing his studies and his collection of folk materials that no one else had ever thought to compile. After his death, his paper airplane collection went to the Smithsonian for their aeronautics wing.

To step into the cosmic scholar cottage was to enter a subterranean warren. Some stinky old wood rat lived here, an ignoble-looking creature that turned out (once you passed the impossible test) to be a spirit animal. Smith’s rooms were smudged with sweetbitter smoke. (We later did homage to him in an issue of Bombay Gin, running the musical score to “Marijuana” by the Fugs. All of them had been acolytes of Smith.) Those who remember him around Naropa know he carried a tape recorder, day and night, taking post-Dada multi-track ethno-historic recordings of anything you or anyone else might say, sing, or cry out. He recorded cars, dogs, fireworks, and street singers. He was more fun to smoke a joint with than just about anyone, and of course, in those days pot was illegal.

If Lamborn had prepared us to melt into the countryside when the enemy showed up, and Smith looked like he could hide you in a ziploc bag of mushrooms, people got a different plan of action from Amiri Baraka, a stalwart in those days. Baraka was a friend of Ginsberg’s and Diane di Prima from the fifties, and Ginsberg liked to bait him on Mao Tse Tung (that’s how we spelled it in those days), the Cultural Revolution, or Cuba. Baraka would goad Ginsberg on pot, Buddhism, homosexuality. All done in amused camaraderie, happy admiration, and knowing that friendship went past any differences of opinion in the TAZ. If you’ve never heard a talk by Baraka—jazz, puns, incendiary ideas, phosphorescent flash of poetry, wicked humor—get into Naropa University’s digital archives and listen. Ginsberg would walk around taking constant photographs of Baraka with his Leica, click, click, click, click. Joanne Kyger noted in a poem of 1991 that Ginsberg had been taking snapshots of Baraka “for the past thirty minutes… with the lens cap on his camera.”

Once I took my daughter Althea and Erica Hunt’s daughter Madeline down to Boulder Creek, while poets discoursed under the tent. The girls, six years old, plastered themselves with mud, then flinging their legs and arms wildly danced about. “We are the mudbabies, mudbabies, mudbabies!” they screamed in song. Before I could snare them they raced back to the tent and leapt with hilarity in front of the panel: two creatures of clay risen from earth. “We are the mud babies, mud babies, mudbabies.” Ginsberg loved it, two archaic gnome children raised from the depths of earth. Click click click click. Sadly, after his death, no photos of mud babies could be located among his negatives. Maybe he forgot his lens cap.

And yet, and yet: who knows where poetry would have ended up without the Jack Kerouac School, without the TAZ of those years and our own?

Some highlights of TAZ summers under the tent. Diane di Prima exhorting students to buy up obsolete printing equipment, put it in working order, publish your own work. Amiri Baraka detailing how you take government grants to buy video monitors for your schools, then throw out the propaganda tapes that arrive with the gear. Ed Sanders playing his musical polka-dot tie, and asking, how can you hope to elect a President, if you can’t put into office a city official who will repair the busted curb down by the gas station. Harriet Mullen on how she kept dodging the labels critics tried to put on her—experimental, Black, vernacular, language poet, woman, etc., etc.

Some highlights of TAZ summers under the tent. Diane di Prima exhorting students to buy up obsolete printing equipment, put it in working order, publish your own work. Amiri Baraka detailing how you take government grants to buy video monitors for your schools, then throw out the propaganda tapes that arrive with the gear. Ed Sanders playing his musical polka-dot tie, and asking, how can you hope to elect a President, if you can’t put into office a city official who will repair the busted curb down by the gas station. Harriet Mullen on how she kept dodging the labels critics tried to put on her—experimental, Black, vernacular, language poet, woman, etc., etc.

Once Frank Chin gave a wildly enraged, spitting critique of Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior. His fury and conviction, the foam at his mouth, his fury at what she had done in her book, had all of us back on our heels. Was this the place to cast noted books into the brimstone and flames? I was the panel moderator. Sitting next to Chin I leaned over to see the notes in his three-ring binder. They were old, yellow, soiled, curled. He had fingered them for how long? He’d been doing this same talk for years? Everywhere he went? The thing was a performance! His eyes bulged, his face grew purple, his veins stood out!

I wondered if Chin and Kingston had written it up together. I wondered if they might be married. Maybe Chin was the prototype for tripmaster monkey in her recent book, running through Chinatown on acid, hurling wisdom at the tourists?

Miriam Patchen came out for a week of tributes to her dead poet husband. We had a show of Kenneth Patchen’s picture-poems, brought on the airplane, from the library at Santa Cruz by Rita Bottoms. Patchen had the piss and vinegar of the Old Left. She spoke truly and didn’t give a rat’s ass about how it made you feel. Afterwards, she and I wrote letters. Hers always opened greeting me, “Schelling, are you still at that college? It’ll ruin your poetry.”

And yet, and yet: who knows where poetry would have ended up without the Jack Kerouac School, without the TAZ of those years and our own?

Here I end this brief “snapshot memory” tour of The Naropa Institute of yore; the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics; the four-week Summer Writing Program under the brow of the Southern Rocky Mountains. All the old timers! Ginsberg, Kyger, Lamborn, Baraka, di Prima, Lorenzo Thomas, Paula Gunn Allen. How many are safe in heaven dead? Anne Waldman’s with us. She will recall these snapshots. Her lens will see things different than my quick notes. And I must recall one annual ritual, held at orientation for each year’s Summer Writing Program. On day one, Bobbie Louise Hawkins would carefully train the whole group how to field strip a cigarette. Her West Texas drawl. Her laconic, precise pacing. The unnerving serious demeanor. The way she looked you dead in the eye. The insistence that one cigarette butt on the grass could destroy the Summer Writing Program, bring the tent down, ruin everyone’s poetry. First, she instructed, you empty the unburnt tobacco onto the grass by rolling the thing in your fingers, then peel off the paper, then you put away the scorched butts….

Smokers carried a Sucrets tin in which to place their dead butts.

The dead poets walk among us with their words.